Why is it that groundbreaking, world-changing products so often originate in the United States? I’d argue the case of Aereo vs. Old-School Television provides a good clue. The founders of Aereo had a clever idea: give live television online to people who don’t want to pay for traditional TV access, which in the U.S. often requires a monthly cable or satellite package of $50 or more. Basic channels like ABC, CBS, NBC, and PBS should not entail extra payments, Aereo reasoned, as they are freely available by antenna. So Aereo gave each and every one of its customers a separate mini antenna, as if that person had put it up on the roof of their building – and that way the company hoped to outsmart the law, cable providers, TV stations, and pretty much all of Hollywood. Not so. Aereo’s whole business idea was effectively shot down when the Supreme Court ruled that the company had violated copyright law.

It was a bold bet to begin with, given the many powerful players that this tiny startup was challenging – yet, tellingly, Aereo found plenty of investors willing to fund this daring venture. Born in 2011, the company raised $97 million in less than three years from various organizations and people with deep pockets who shared the founders’ vision (or were simply looking for the Next Big Thing) and didn’t hesitate to place a very expensive wager on a very different future.

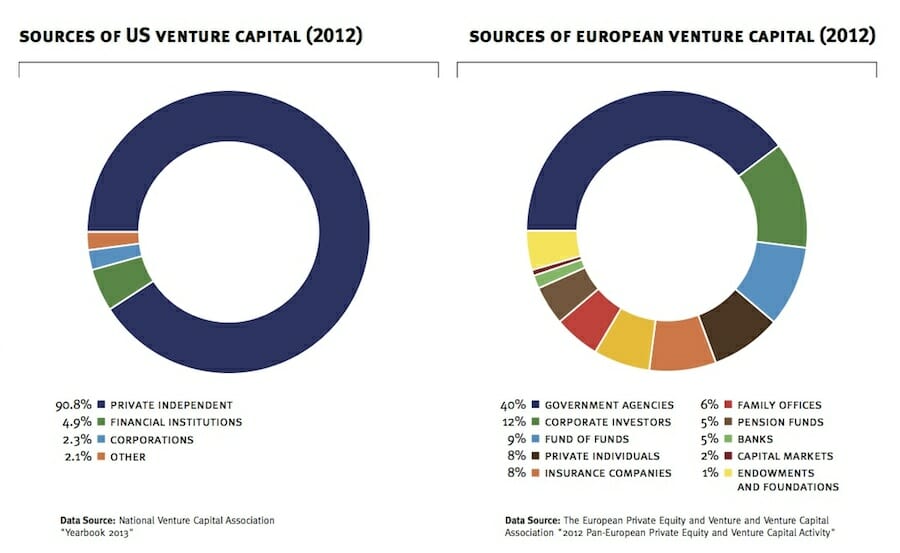

Disruption, the success of new ideas, requires risk-taking – not just by entrepreneurs but also by their financial supporters: family members, angel investors, venture capitalists. Members of the establishment that are willing to buy into the founders’ vision of change, success, and reward. In the U.S. – and especially Silicon Valley – this is far more often true than in other parts of the world. A recent study by the Bay Area Council Economic Institute, which compared investing patterns in Europe and the Bay Area, showed that in the U.S., the vast majority of startup funding (almost 91%) comes from private investors; in Europe, the biggest chunk is government money.

“It’s definitely a fast pace here [in Silicon Valley]”, says Tracey Grose, co-author of the study. “And a very important factor is the openness to taking risk. You don’t see that to the same degree in the rest of the country and certainly not in Europe.” In fact, east of the Atlantic even venture capitalists often shy away from actual risk-taking. Over and over, European founders keep telling me that they feel a need to move to California in order to realize their entrepreneurial visions.

Take Timbuktu from Italy, a startup specializing in educational children’s apps for tablets and smartphones: In Italy, “the reception was that we were working on something nice and cute – but not fundable”, says Elena Favilli, who founded the company along with Francesca Cavallo. “We tried for almost one year.” Then they headed to California, as Timbuktu had been accepted at 500 Startups, a popular incubator typical of Silicon Valley’s ecosystem of innovation. In addition to basic funding, 500 Startups provides help from other entrepreneurs. “Some of them are ahead of you and you can learn from them”, says Elena, “and the amount you learn can push you much faster.”

By now, Timbuktu has investors from Italy as well and even found partners in the traditional publishing industry. But first the company had to prove that it could be successful. “We felt we needed some validation overseas in order to be considered credible”, says Francesca Cavallo.

Obviously, for the European economy this is the perfect recipe for always staying a few steps behind. If founders need to prove first that their ideas will work, before even VCs are willing to support them, real innovation will continue to predominantly come from abroad. The necessary change is a cultural change – which makes the challenge harder. In America’s startup world, failure is a feature, not a defect. It’s generally accepted that only a handful of ideas, a small number of companies, will be successful. Any early-stage investor knows that the likelihood of hitting the jackpot is small – and yet they keep trying. Aereo may effectively be dead, the investors got burned; still, there’s a good chance that the next challenger to the establishment will be born in the U.S.A.