Image courtesy of the Foundation Lindau Nobel Laureate Meetings

For much of his professional life, Harvard economist Eric Maskin has been studying which rules should apply in the economy so that everyone benefits in the end. In 2007, he was a co-recipient of the the Nobel Prize in Economics, together with Leonid Hurwicz and Roger Myerson.

In recent years, Maskin has turned his attention to change management in business, politics and society.

Strengthening democracy against the corrosive effects of populism and polarization is a particular concern to Maskin – because without a vibrant democracy, he argues, there can be no vibrant economy either.

I had the chance to interview Prof. Maskin at the Lindau Nobel Laureate meetings and get his insights about a wide range of topics – from reforming our voting system to AI, corporate leadership and finding economic incentives for mitigating climate change. The German version of this interview was published in the magazine WERTE.

You’re saying that we’re voting the wrong way. What are you referring to?

In democracies, we want a majority – not a minority – of people to elect their office holders. But under plurality rule (where each voter votes for one candidate, and the candidate with the most votes wins), it’s easy for candidates to be elected with well below 50% of the vote.

Can you explain how this can happen?

Let’s assume you have three candidates in an election, and one gets 34% while the other two get 33% each. Then, 34% is enough to win the election – even though the overwhelming majority of votes went to the other candidates. Indeed, it could well be the case that most people prefer both of the losing candidates to the winner. But since the losers split the vote, the least popular candidate gets elected. That seems profoundly undemocratic.

“Independent candidates rarely get elected, even though there’s a gaping hole in the middle of the political spectrum.”

Where do you see the biggest need for reforms?

In American politics the two major parties, the Democrats and the Republicans, have moved farther apart. In this atmosphere of radicalization and polarization it would be desirable if independent, more centrist candidates could enter races and get elected. But the plurality voting system makes it difficult for them because it is risky for voters to support third-party candidates; they often think they’re just throwing away their vote (since they doubt that many other citizens will support these candidates). Therefore, independent candidates rarely get elected, even though there’s a gaping hole in the middle of the political spectrum that is not being filled.

Is this a specifically American problem?

No, the distortions I have described can also be observed in Europe. For example, presidential elections in France are decided by runoff voting (where, if no one gets a majority in the first round, the two top vote getters go to a runoff). In 2002, a far-right candidate, Jean-Marie Le Pen, got to the runoff because the much more popular candidate Lionel Jospin split the vote on the left with two other candidates.

What would be a better way to vote?

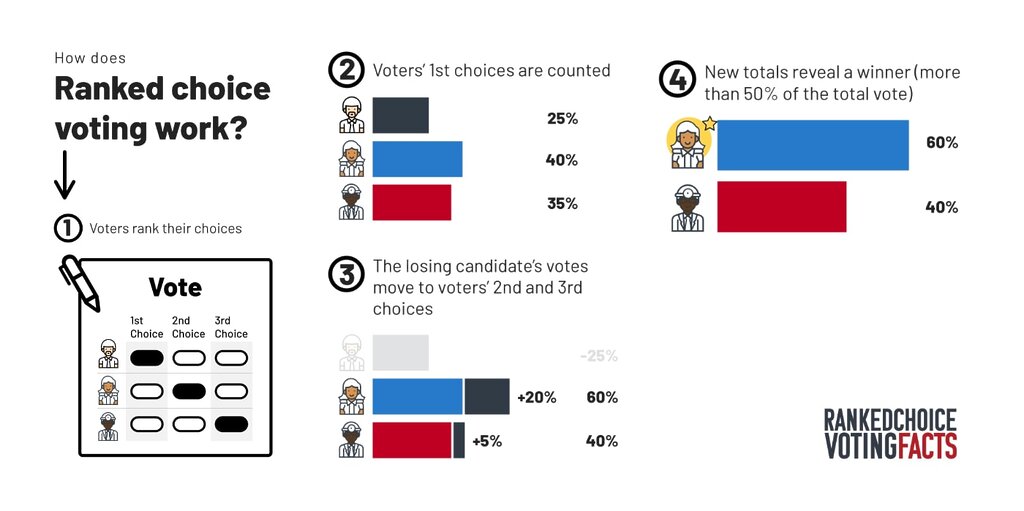

There’s a system gaining ground in the U.S. called ranked-choice voting. Instead of just voting for a single candidate, as under the current system, a voter has the option of ranking the candidates. That means he can say, “I like candidate A the best, but if she doesn’t win, then I want B. And if B doesn’t win my vote goes to candidate C.”

A better way to pick a winner? Ranked-choice voting explained. (Source: Ranked Choice Voting Facts.)

How is the winner determined?

First you check whether some candidate gets a majority of the first-place votes. If so, she is elected. If not, the candidate with the fewest first-place votes is dropped. That candidate’s supporters have their second-place choice shifted into first. We now check again to see whether someone has a majority, and the process of dropping and shifting continues until someone does have a majority.

Why is this superior to prevailing systems?

First, it drastically reduces vote splitting (If a voter prefers A and B to C, then she can rank them both above C; she doesn’t have to choose one or the other. So, C will no longer win because of vote splitting between A and B). Second, it encourages centrist independent candidates to run. With ranked-choice voting, voters will be willing to rank a third party candidate first. If that candidate wins, great. If not, they still have a say among the major party candidates. Thus, the system fights polarization by giving independent candidates a better chance of winning.

What chance does this new model have of disrupting the status quo?

I think it’s catching on in the U.S. To begin with, almost 50 American cities now use this method for electing city officials, like mayors – including New York City and San Francisco. But more importantly, three states, Alaska, Maine, and Oregon, have adopted it for essentially all their elections. And other states, such as Vermont, Nevada, and Minnesota, are considering doing the same thing.

Are we seeing any consequences of this change?

Yes, we are. Take the 2022 special election in Alaska for the House of Representatives, for example. Trump backer and former Alaska governor Sarah Palin lost to Mary Peltola, even though Peltola was considered an underdog before the election. She prevailed because many supporters of a third candidate, Nick Begich, placed her ahead of Palin on their ballots (so when Begich was dropped, their support went to Peltola).

Where does this momentum for change come from?

From the people themselves, as in referendums to adopt ranked-choice voting. For voting reform, change almost has to come from the people – because incumbent politicians don’t have much motivation to change the system. After all, they got elected under the old rules. So, they’re reluctant to change them.

“Unfortunately, in the digital age, we have seen a slowdown in innovation, especially in the technology sector.”

Can we apply this insight to the business world? Does the impulse to change have to come from the bottom up as well?

In the corporate world, the need to change typically comes from competition. Yes, you may be the market leader in your industry right now, but there will always be startups and other companies who are who are nipping at your heels – and unless you innovate they’re going to overtake you. Competition is an enormous spur to innovation.

Does this classic economic insight still hold up in the digital age?

Unfortunately, in the digital age, we have seen a slowdown in innovation, especially in the technology sector. Google is monopolizing search engines (perhaps generative AI will change this), Amazon is monopolizing online marketing, and the power of digital platforms in general means that would-be competitors have a hard time breaking in. That’s a big problem. Because when there’s not much competition the economy is going to be less innovative.

“Artificial intelligence is going to affect everybody. I don’t think any company can afford to ignore it.”

Many people expect artificial intelligence to result in a reshuffling of the deck. What’s your take on this?

Artificial intelligence shows that some kinds of innovation need not come from humans. At this point, AI systems can learn and improve on their own. They don’t need a human programmer to make the improvement for them.

What does that mean for business leaders? Should a typical German SME bother with AI?

Artificial intelligence is going to affect everybody. I don’t think any company can afford to ignore it, because almost every company performs tasks that eventually can be done by machines. That is not to say, however, that we won’t have human beings working anymore, because just as in the Industrial Revolution, there will be new jobs created; jobs where people collaborate with AI, rather than being replaced by it.

What’s your advice to corporate leaders who feel overwhelmed by the pace of change?

There is a Chinese company named Haier, which I think has a very interesting approach. It’s a giant in home appliances, and it has an unusual corporate structure: there’s top management and there are many small productive units, hundreds of them. And almost nothing in-between. There’s no middle management. And the productive units do all the innovating. In fact, they are almost completely autonomous.

The idea being?

The argument for this structure is that management probably doesn’t know what innovations are going to be important for appliance production – but engineers might. So let the engineers make the innovative decisions, and that way top management doesn’t have to concern itself with change.

What’s the job of top management in this structure?

Their task is to preserve the Haier brand, to preserve Haier quality. In addition, they make sure that there’s capital available to the engineers so that the innovative units can keep growing. But they don’t interfere with the important productive decision. That’s done by the productive units, which sell directly to customers; they don’t go through top management. If I, as a customer, want a particular appliance, I speak directly to the engineers.

“It’s not enough to stop carbon emissions; we also have to remove them. And the beauty of the carbon tax is that it gives everybody the incentive to do both things.”

How does the company develop a coherent strategy?

In a sense, you don’t need corporate strategy at the top anymore. Top management is there to support the innovation and strategic ideas coming out of the productive units. For companies that need to keep up with the fast pace of technological progress, this structure brings major advantages. In those sectors there’s no reason to expect managers to know what’s important and what’s not – particularly managers who are not engineers themselves. I expect that this model might well catch on. It’s certainly been very successful for Haier. And it’s been studied by business scholars and other academics, because it’s potentially so powerful.

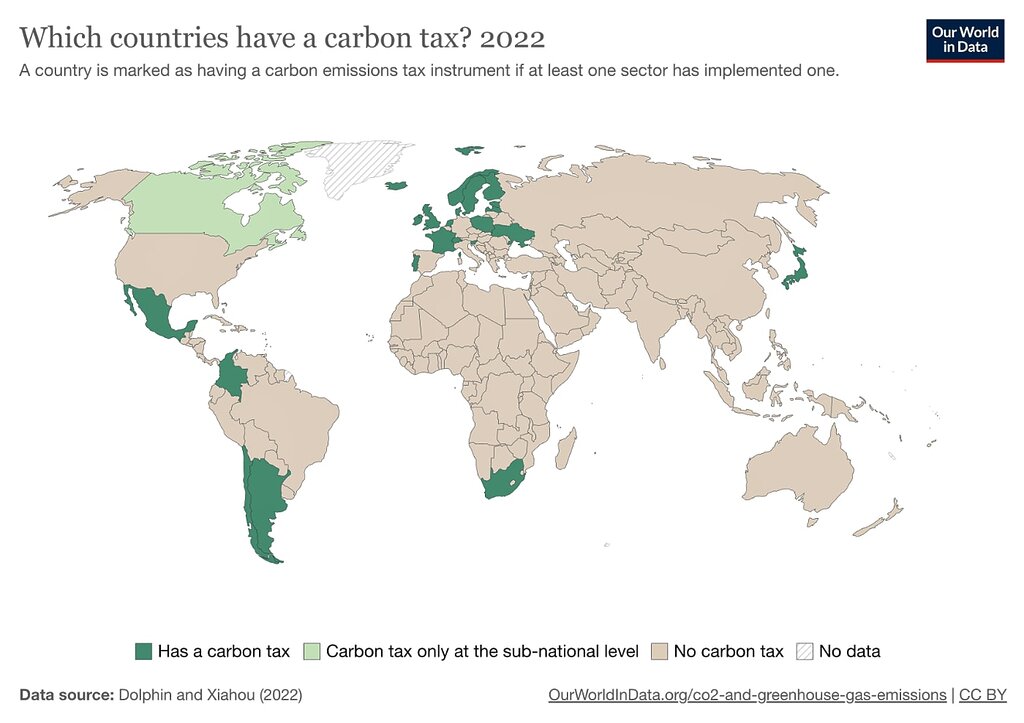

Global problem, local tinkering: Only a handful of countries worldwide levy a tax on carbon emissions, as this chart by Our World In Data shows.

We urgently need innovative solutions with respect to climate change as well. Do you see any promising approach to make the global economy more sustainable?

Economically speaking, there’s a very powerful tool that could be used – and that is a global carbon tax. That is, if you emit carbon dioxide into the atmosphere you have to pay a tax in proportion to your emissions. But equally important: if you remove carbon dioxide, if you figure out a technology for taking carbon out of the atmosphere, you will be rewarded in proportion to your removal.

Both parts are important because it’s not enough to stop carbon emissions; we also have to remove them. And the beauty of the carbon tax is that it gives everybody the incentive to do both things. So with one simple change we would be a long way down the road toward solving the problem.

If it’s seemingly so simple why don’t we have this system yet?

It’s not because the idea isn’t well known; it was dreamed up years ago. But there’s a political obstacle. No country wants to introduce a carbon tax unilaterally. Everyone wants to make sure that other countries do it too. And so until you have collective action, until you have an international treaty in which all countries – or most countries – agree on the carbon tax, it won’t happen.

Do you see a chance to make it happen anyway?

One way is through leadership. The United States and China are the two obvious leaders. They emit the most carbon…

…and they’re not exactly on speaking terms, as tensions keep rising.

But they both recognize that climate change is a global disaster waiting to happen. In fact, it’s already happening. And I was encouraged a lot by the fact that the U.S. – finally, after decades – passed a climate bill in 2022. It’s not enough to solve the problem but I’m a great believer in political momentum, meaning once you get something going, you can build on it and do more.

What about China?

China is another question. On the one hand, they are the world leader in developing green energy. They are doing it faster than anyone else. At the same time, they are declining to get rid of fossil fuel energy; in fact, they keep building new coal-fire power plants. And I am very worried about their current President, Xi Jinping. I do not think that he is as forward-looking as his predecessors. His nationalist impulses seem stronger than his inclination toward international cooperation. Still, climate may be actually a good opportunity for the U.S. and China to successfully go back to the negotiating table. The American public definitely is waking up to the idea that climate should be a high policy priority. So perhaps U.S. leaders now have the political incentive to try to get with China to work with them on this.